The Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station captured by Russia is a staging post for “hunting” trips against civilians.

Acting as a base for artillery and a nearby drone pilot school within mortar range, it looms so close to the nearby city of Nikopol that one could almost pat the plant’s unstable nuclear domes.

Nikopol, still held by Ukraine, has seen its population halve to 50,000 since the war began. About 6,500 of those still living here are children.

Lying right on the front line, the city has been attacked every day for the last four years. Roads in are a gamble and gauntlet, a race along icy roads, in hope of avoiding an attack or a freezing crash.

First Person View drones (FPVs) are flown by Russian pilots who can see the streets of Nikopol with the naked eye from the nuclear plant across the river.

But they go one step further to see the look on their victim’s faces when they dive their quadcopter killers onto whomever they choose to die.

Despite this, half of this city’s inhabitants have decided to stay. Hunted as prey, and shelled at random, countless people have been killed by Russia here since 2022, when Vladimir Putin’s forces captured the power station just over the river.

Tens of thousands of Ukrainians are opting live in this place they call home, flitting about the streets like the prey they are and sending their children to underground schools.

On arrival at School Number 6, the vast main atrium is silent but for a few footsteps. Outside, a not-too-distant crack and thump of a drone that has got through the bad weather and hit the city rattles at the hall windows.

A teacher shrugs and leads the way into the cellar to start the day. Its walls are decorated with posters about how to spot unexploded bombs. One shows a red drone with its four engines and gives instructions on how to hide from these new weapons.

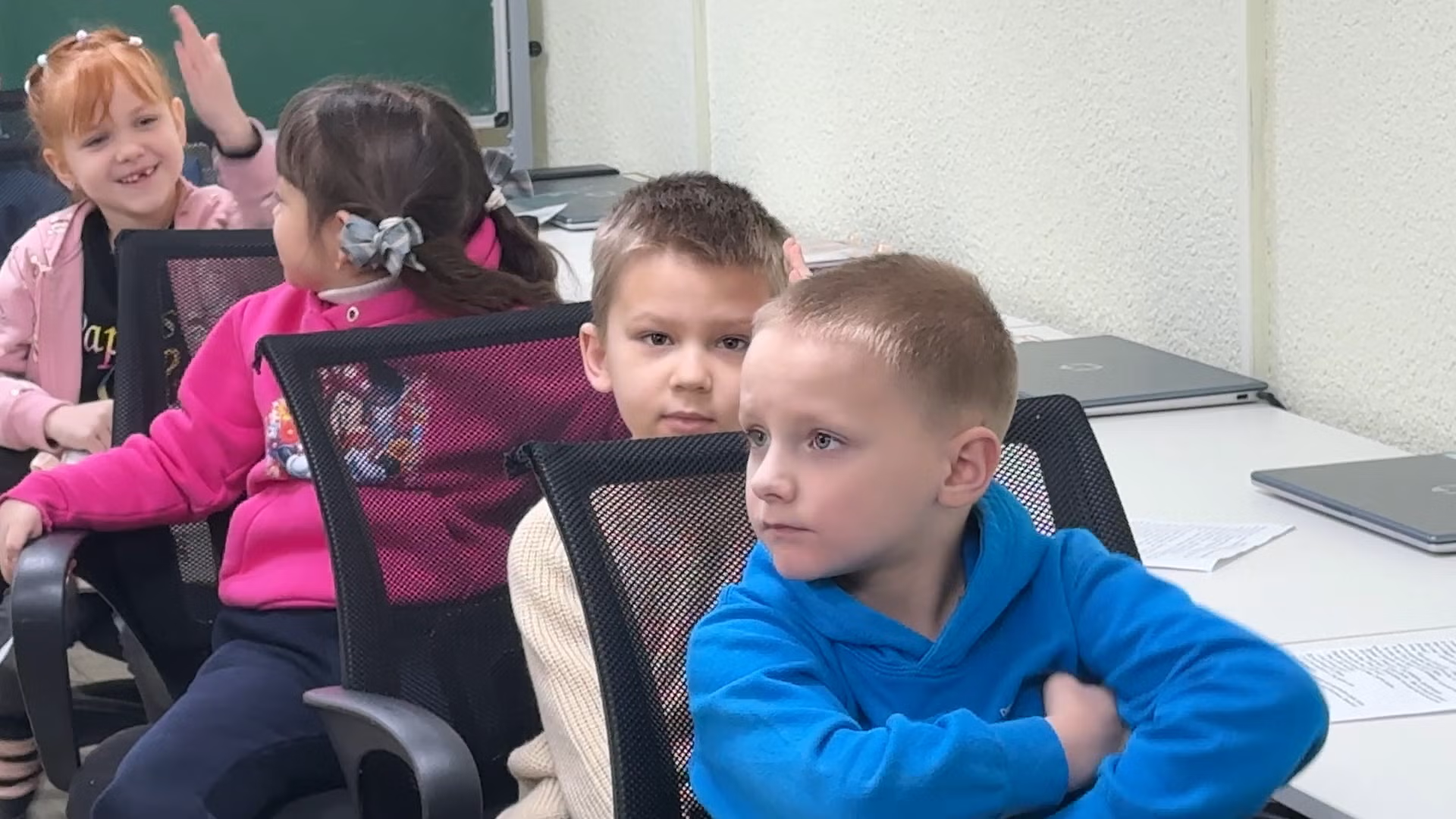

“Good morning!” chime a classroom full of seven- and eight-year-old Ukrainian children in grade two, the UK’s year 3.

Spinning backwards in their chairs to see the visitor in a windowless classroom, they smile and wriggle. Laptops sit on the desks in front of them as their teacher, Iryna Sichkarenko, asks them to recite in English “my name is…”.

This is a warm and safe place where they can learn and hang out with friends. Above ground, in the sunlight, that has been impossible for more than half the lives of this class of 20 kids.

Putin has increased the pounding of civilian targets over the last year. His troops have singled out the port city of Odesa in the far south, Kramatorsk in the north and the energy systems across the country, for especially violent attention.

The Russian president intends to drive Ukraine out of the eastern territories he has already illegally annexed and to cripple the country in the long term.

So-called “peace talks” run by the US, which has adopted a largely pro-Russian position and demanded concessions from Ukraine in return for mineral rights and a cease-fire, have delivered nothing.

In places like Nikopol, though, the steady state of attacks has changed only with the advent of the deadly-accurate drones.

On the battlefield, statistics have been upended – drones kill about 80 per cent of the people they hit and wound the rest. Guns and old fashioned artillery have statistics the other way around.

For these children, underground school is a lifeline to normality in a very abnormal world.

“Here we can discuss our dreams, weekends, plans, interests. It’s live communication and we value every minute we can meet, draw something, do some crafts or organise some kind of party,” the teacher says.

They get two morning sessions like this a week. The rest of these children’s lives are spent at home and studying remotely as if the Covid pandemic never ended.

Bohdan is seven. He reads out loud with confidence and dramatic inflection. It’s a story about Grandpa Frost because in the lives of these youngsters there is little space for whimsy.

“A small old man with a grey beard was sitting on a bench and drawing something in the sand with an umbrella. ‘Move over’, Pavlyk said to him and sat on the edge,” Bohdan’s fingers trace the words as he talks.

Lilia, also 7, also reads from the book: “‘There is such a magic word…’ Pavlyk opened his mouth wide. ‘I will tell you this word, but remember: you must say it in a quiet voice, looking straight…’.”

Pavlyk is an angry character. Anger is an instantly recognisable theme for these kids and something that takes hold of some of them and won’t let go.

Bohdan’s mother Inna Liaskovska says her son loves school but suffers from anxiety.

“Sometimes he gets nervous. He can react very childishly and he can’t hold his emotions,” she explains.

“He needs to release them. He releases them through hysterics, shouting for no reason. You tell him ‘no, don’t do it’, and for him it’s like an emotional explosion.

“He doesn’t want to listen to anyone, doesn’t want to do anything – he just closes off, he has such hysterics.”

That is not surprising because she says she feels like they are being hunted every time they leave their flat.

“Last summer as soon as we went out, and it’s a miracle that we were still near the house, we had to run back to hide in the entrance, because we saw a drone flying past the house…

“So, I believe that yes, this is a targeted safari on people. There was another case: we were coming from school and, again, an FPV drone was flying. We hid behind the trees so that it would fly past, and we could get home safely.

“When we we came home, my boy asks, ‘Mom, is everything okay?’ I say, ‘Everything is okay.’ Like, ‘don’t you worry’. But none of us is safe.”

Inna says she and Bohdan did leave Nikopol when the Russians first captured the power station opposite in 2022. They moved to safety in Poland for three months, but came back.

“Home is home. It was difficult there. Not as much physically as it was spiritually difficult. With a child, alone, without my husband. So we returned home to Ukraine.”

The underground school, built and maintained in large part with funds from Street Child International, offers counselling, social support, supplementary education and meals to chatter over to children.

Anatasia Ukhan, Street Child’s local manager, is a teacher and has a 13-year-old too: “These children don’t know how to communicate with each other; they are closed.

“Especially teenagers… With them, it’s the hardest. Small kids, they are still sincere and open, and they hope for the best.

“But the teenagers, grades 6 to 9, are much more difficult. They are closed. They don’t talk to anyone. So, unfortunately, desocialisation is happening. It will be a huge problem in the future,” she warns.

Another underground classroom holds about eight young teenagers. They sit, as people their age often do, awkward, muted. Fifty three of the 58 schools in the city have been hit by Russian bombs and a couple more explosions can be heard hitting somewhere downtown as we visit.

Sophia Prokopenko, 15, says they are all experts at how to react depending on whether it is a drone or artillery. They endure incidents every day, she says.

“You go out into the street, and you can see or hear a drone. You go to training – a drone. If not a drone, then artillery.

“To training, to the store, to the pharmacy, just going out to throw out the trash – they are everywhere,” she adds.

She insists that the school is their salvation.

“We just can’t gather in another place. If we go to a cafe – a drone, FPV, or artillery – and that’s it; there’s no cafe and no people. School is the only place where we can hide from this cruel world.”

So why does she not also leave with her family?

“Of course, it’s very scary, very difficult to constantly be in such a state,” she explains. “Many have left—abroad, to other cities, to relatives, to Western Ukraine – but still, the best place remains at home, no matter how hard it is here.”

It’s not clear that Putin quite understands that.